"No one should be subject to degradation and violence just because they are women"

Based on reports and statistics, Cho Nam-Joo painted a portrait of the life of Korean women today, with which "as many women as possible could identify". Notícias ao Minuto spoke with the author of 'Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982', whose Portuguese translation hit the bookshops on the eve of International Women's Day.

© Cho Nam-Joo/Goodreads

Cultura Literatura

The first edition of ‘Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982’ was published almost in tandem with the rise of the #MeToo movement, which spread across the world in mid-2016. Based on her own experience as a woman who left her job to become a housewife after the birth of her daughter, South Korean author Cho Nam-Joo transposed to paper the reality faced by her countrywomen, although any woman can identify with the experiences of the protagonist.

The book, which has been translated into more than 20 languages and sold more than two million copies worldwide, arrived in Portugal on the eve of International Women's Day, celebrated annually on March 8. Notícias ao Minuto spoke with the writer about this third novel that paved the way for a new wave of feminism in South Korea, driving debates on inequality and gender discrimination not only in that country, but in the world.

Using reports and statistics, Cho Nam-Joo painted a portrait of the lives of Korean women today, with which "as many women as possible could identify". And, although the country continues to adopt a "very tolerant stance towards sexual crimes", the author found that, if before "there was a sense of defeat and cynicism", today women know that their voices "make a difference".

No one should be subject to degradation and violence just because they are a woman. The frustration, exhaustion and fear that come from being a woman. I wanted to write a story about something that is so common and ordinary, but that should not be taken for granted

What motivated you to write about the problems and discrimination that women face on a daily basis?

In Korea, around 2015, there was a huge wave of what I would call a feminist ‘reboot’. At the time, a lot of media and the internet were ridiculing and putting down women, and there was even a new term called ‘mamchung’ which compared mothers to maggots. Illegal and sexually violent spycam videos on Korea’s biggest porn site were exposed and women started protesting, and I think I wrote this novel in the midst of that.

I felt that no one should be subject to degradation and violence just because they are a woman. The frustration, exhaustion and fear that come from being a woman. I wanted to write a story about something that is so common and ordinary, but that should not be taken for granted.

You wrote this work in just three months, but it is full of statistics that prove the various levels of discrimination in South Korea. Was it easy to put on paper what you feel on your skin?

I wanted the novel to serve as an impartial record of the lives of Korean women today, and I wanted to make sure that it wasn’t just fiction, a made-up story, but that it was real for someone. To do that, I needed objective data to support the story, and I used reports and statistics from the media.

Of course, ‘Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982’ has its flaws and limitations, and it is only natural that there should be critical appreciation, but I can’t help but feel helpless towards those who ridicule and condemn it without reading it properly

I majored in Sociology in university and I worked as a scriptwriter for a TV show before I started writing novels. I follow the news and I have a habit of looking up the sources of the statistics quoted in reports. However, my other novels are in the so-called "traditional novel format". For the story of ‘Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982’, I found this narrative style effective and I actively cited sources and statistics.

Kim Jiyoung could be any woman; even this name was chosen on purpose, since it is a very common name in South Korea. How was the book received by women? And by men?

Female readers often talked about themselves: their experiences as daughters, students, employees, mothers. [They shared] thoughts, doubts and questions they had when they saw the women around them... Even in press interviews, female journalists talked about their own stories before I could even ask them questions, such as the fact that they had left their children with their mothers for the interview, or the difficulties they faced in a male-only organisation. I thought, "This is the kind of novel that makes us want to talk about ourselves, and I want to keep women talking”.

In the early days after the book was published, male readers told me that they had gained a deeper understanding of women's lives, and the politicians who publicly expressed their appreciation and recommended it were all men. Then, as the novel became synonymous with "women's voices", "women's narratives" and "feminist fiction", I felt the backlash growing. Of course, ‘Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982’ has its flaws and limitations, and it is only natural that there should be critical appreciation, but I can’t help but feel helpless towards those who ridicule and condemn it without reading it properly.

Did you think about the repercussions that the work would have internationally when you wrote it?

When I wrote the novel, my goal was to get it published. When the film came out, the director said that he felt that the narrative of ‘Kim Ji Young, Born in 82’ had a life of its own. When I see the novel being translated and published in various countries, I think to myself, "I want the story of 'Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982' to spread further, to get people talking, to get people thinking, to get people arguing, to get people existing." I think ‘Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982’ is braver and more enterprising than I am.

© Porto Editora

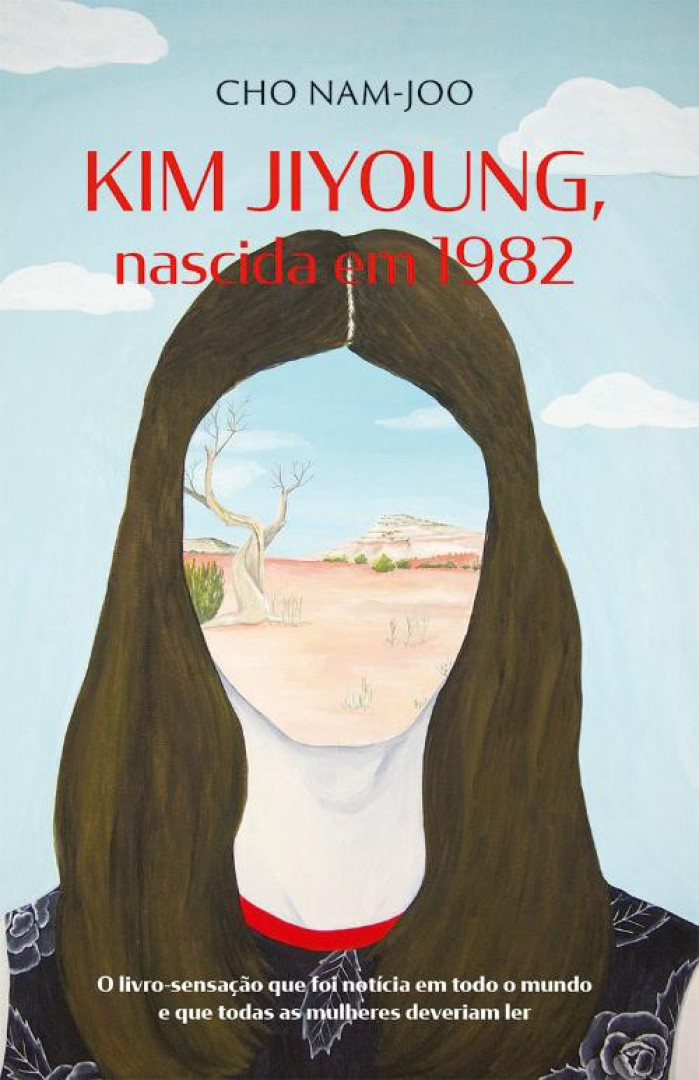

The cover of the book is also symbolic, given that it depicts a woman without a face. What other symbolisms did you want to convey?

In ‘Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982’, I wrote about the universal experience of women as an anthropological report. Kim Jiyoung is a canvas of emotions and experiences, and I wanted readers to be able to put themselves, and the women around them, on that canvas.

You said that, if you were a boy, your uncle – who already had five daughters – would have adopted you. What aspects of this story are autobiographical?

When composing ‘Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982’, I gathered experiences left by women on various social media, cyber cafes and bulletin boards, and selected episodes from articles, interviews, webzines and books about women's lives and work. I tried to write something that as many women as possible could identify with, and as a result, I have similar experiences. For example, the order of class numbers in school, sexual harassment on a large and small scale, support at home that focused more on sons than daughters and career interruptions after having children.

According to the data you presented, it was common for women to have abortions when they found out they were pregnant with a girl. How do you view this type of misogyny rooted in women themselves?

We all internalise the norms and values of the society we live in. If we are born, educated and live in a patriarchal and masculine society, even a woman will have patriarchal and masculine values.

In the 1980s, unlike today, Korea had a birth control policy due to concerns about population growth. At a time when people had only one or two children, the preference for boys remained, and when advances in medicine made it possible to identify the sex of the foetus, the phenomenon of son preference was born. I think that aborting >

Descarregue a nossa App gratuita.

Oitavo ano consecutivo Escolha do Consumidor para Imprensa Online e eleito o produto do ano 2024.

* Estudo da e Netsonda, nov. e dez. 2023 produtodoano- pt.com